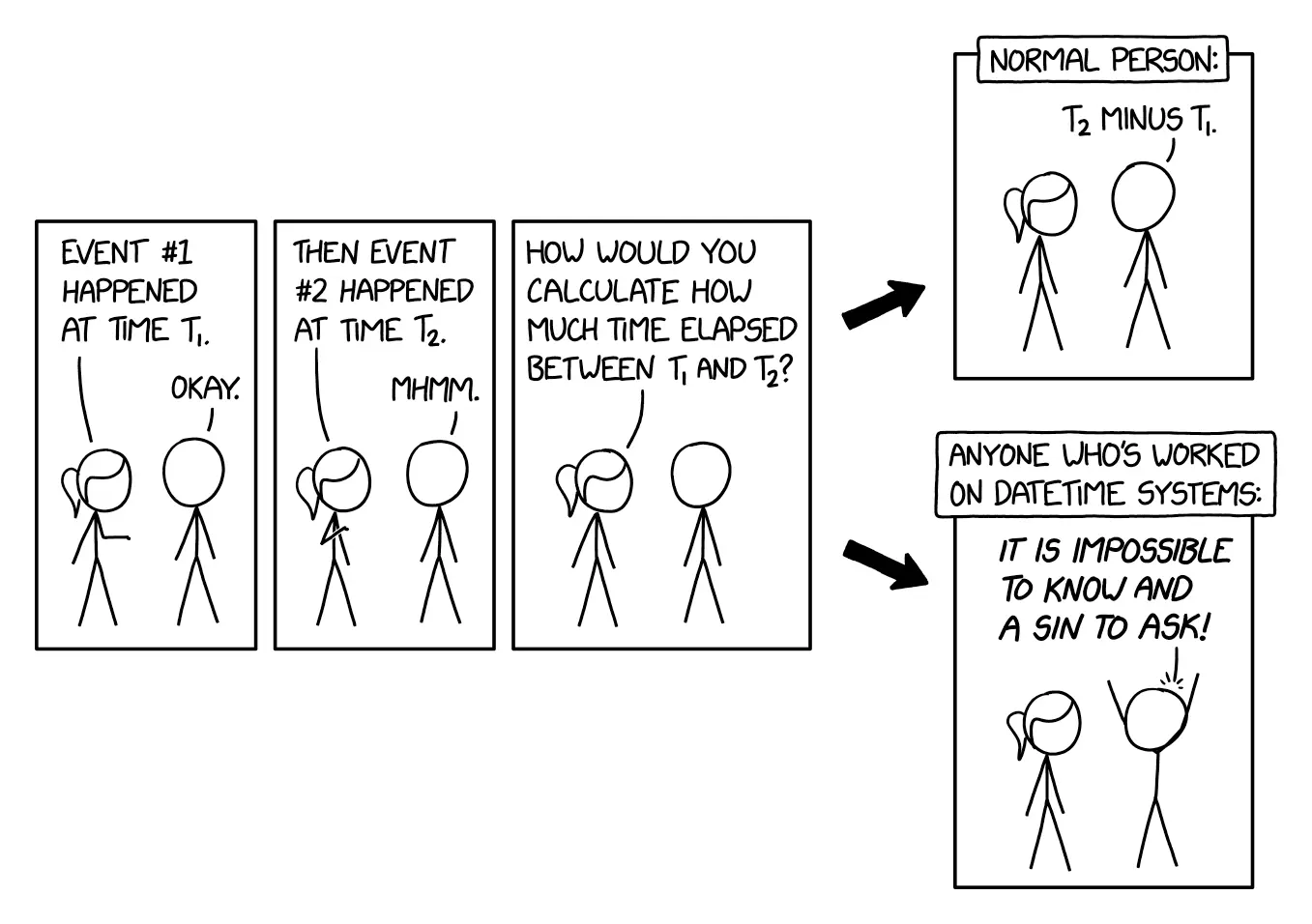

If I were to ask you “How many seconds are in a day?”, you would probably either know an answer off the top of your head or could easily calculate one. Your answer would almost certainly be “86,400”. Your answer would be wrong.

Well, kind of. It depends on what you meant by “second”.

A Tale of Two Seconds

Natural Seconds

In elementary school, you learned that there are 24 hours in a day, 60 minutes in an hour, and 60 “seconds” in a minute. This is the common definition of a second, and it’s the only one most people learn. There are several names for this second, including “civil second”, “solar second”, and “UT1 second”. I’m going to call it the “natural second”.

The natural second has an exact-valued relationship with the length of the day (or, more precisely, the duration of Earth’s rotational period). Specifically, there’s an 86,400:1 relationship between the length of the natural second and the length of the day. Using this definition of “second”, your answer to my original question is correct. However, the natural second is not the officially “correct” second.

Caesium Seconds

Both the SI (metric) system and the customary (U.S.) system define all of their units in terms of the second, one way or another. The SI meter is defined as “the distance that light travels in a vacuum during 1/299,792,458 of a second”. If you didn’t know how long a “second” is, you also wouldn’t know how long a meter is, so the definition of a meter relies on the definition of a second.

Even units that aren’t directly defined via seconds can still be reliant on it. For example, the customary foot is defined as exactly 0.3048 meters, so because it’s based on meters and meters are based on seconds, the customary foot is ultimately based on seconds. Likewise, because the SI kilogram is defined in terms of the speed of light, the Planck constant, and the SI meter, it too is based on seconds. The customary pound is defined as exactly 0.45359237 kilograms, so it relies on kilograms which rely on meters which rely on seconds. Every unit ultimately relies on the second. Because of this, it’s absolutely critical that we know exactly how long a second is.

The natural second is not good enough for this. The natural second is defined in terms of the length of the day, and the length of the day changes a tiny, tiny amount every day (mainly due to the Moon’s gravitational pull gradually slowing Earth’s rotation over the course of millions of years). Because of this, the definition of a natural second is ever so slightly different every day. This is obviously unacceptable; nobody wants to update yardsticks because the definition of a foot changed.

So scientists decided to use a unit of time that doesn’t ever change: the ground-state hyperfine transition of a caesium-133 atom. That’s a lot of jargon, but all you need to know is that it’s a very specific duration of time that is extremely stable and can be reproducibly measured using laboratory equipment. The only problem is that it’s very, very, very small: approximately 9 billion times smaller than a natural second. So the solution was to define “second” to mean “the ground-state hyperfine transition of a caesium-133 atom multiplied by exactly 9,192,631,770”. This definition also has several names, including “SI second”, “atomic second”, and “proper second”. I’m going to call it the “caesium second”.

The difference

A caesium second is approximately equal to a natural second, but it’s not exact. The percent difference is usually around 0.000002%, which is so small that the two seconds are often considered “close enough”, the subtle differences between them are ignored, and the two are used interchangeably, despite being fundamentally different. More on that later.

Anyways, if we define a “second” to mean a caesium second, the answer to “How many seconds are in a day?” is approximately 86,400.002.

Why it matters

This might sound like pedantic hair-splitting. And okay, it kind of is. But the difference between caesium seconds and natural seconds does have real consequences.

Almost every internet-connected time display (including your phone/laptop/whatever) uses caesium seconds. The second hand on a smartwatch ticks forward every caesium second, not every natural second. This means that 86,400 ticks of a smartwatch is slightly less than the time it takes for Earth to complete a full rotation. Over a long enough time period, these errors compound, and your clock will drift out of sync with the Earth. As of 2026, the errors should amount to 27 (caesium) seconds of difference over the past 54 years.

And yet, your smartphone stays almost perfectly in sync with the Earth. This is because of the monstrously complex idiosyncrasies of Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).

UTC tries to do two things simultaneously: use caesium seconds, and make the Sun’s zenith always occur at 12:00. These two things are fundamentally incompatible, so UTC requires lots and lots of special rules, edge case handling, and adjustment via committee that make it a nightmare for everyone.

Leap Seconds

To solve the desynchronization problem, UTC just lets the errors build up until they amount to one caesium second’s worth, and then they announce a leap second to bring the difference back down. UTC gives 6 months of warning before each leap second, and then leaves the implementation of that leap second as an exercise to datetime programmers around the world.

Because datetime programmers can’t agree on how best to handle leap seconds, different systems handle them slightly differently. Some systems display an extra second at “23:59:60”, some display “23:59:59” for two whole seconds, some “smear” the leap second throughout the day, and some just blank out entirely during the leap second. Some systems ignore leap seconds completely because they’ve decided that the errors are insignificant enough that they aren’t worth handling properly.

Almost everybody hates leap seconds, including Google, Amazon, and Meta. Even BIPM (the organization responsible for UTC) is trying to make leap seconds less frequent as part of Resolution 4.

Oh, and also it’s possible that UTC will add a negative leap second at some point in the near future, so that’s fun.

Leap seconds are a confusing, inconsistent mess that should be abolished.

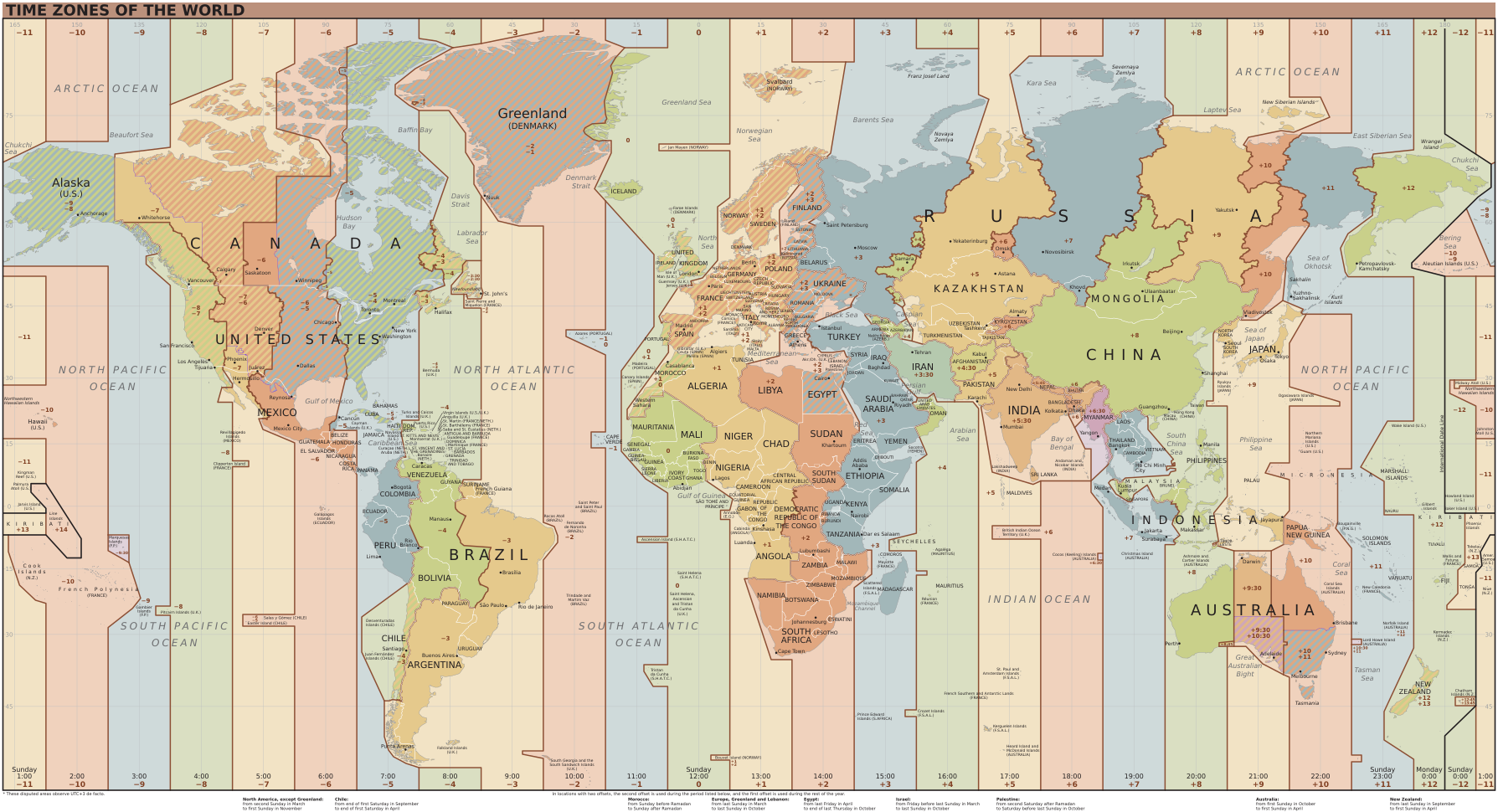

Time Zones

The image above is a map of UTC’s time zones. Each zone represents a different offset from UTC (which is “zeroed” on the Greenwich Royal Observatory in England). Because “noon” is based on the position of the sun, which varies by longitude, different longitudes experience noon at different times. Without time zones, noon would occur at different times throughout the world, which would violate UTC’s goals. So UTC offsets the time by discrete increments depending on where you are on Earth.

The whole purpose of time zones is to correct for the sun’s position varying by longitude, so time zones should be based entirely on longitude. They should be straight, parallel ribbons. In reality, time zones contour to geographical and geopolitical borders for political reasons, which results in the wacky and uneven zones that you see above.

Most time zones are offset from UTC by a positive or negative whole number of hours, but even this broad statement has a few asterisks. Examples include Indian Standard Time, which is 5 hours and 30 minutes offset, and Nepal Standard Time, which is 5 hours and 45 minutes offset.

Because of time zones, a contextless hour (e.g. “2:00”) conveys literally zero meaning about what hour it’s referring to globally. The whole point of saying “2:00” is to refer to a specific hour, but it’s meaningless without also including a time zone.

Even if time zone ribbons were geometrically perfect, they would still have a fundamental flaw: they’re ribbons. Most time zones are 1/24 of the circumference of the planet in width, so the sun’s position varies by an entire hour across a single time zone. Rather than being global/stable or being fully Earth-tracking, time zones are a weird half measure that have the disadvantages of both.

Time zones are a confusing, inconsistent mess that should be abolished.

Daylight Saving Time

To make UTC’s time zones even worse, sometimes the offset changes by an additional hour for daylight saving time (DST).

In addition to intentionally creating inconsistencies depending on the time of year, DST also adds even more inconsistencies depending on location. Within a single time zone, some countries respect DST while others don’t. Within countries that are split across multiple time zones (like the U.S.), some regions respect it and others don’t. There’s no rhyme or reason to this, so you just have to keep a list of regions that do and don’t use DST. Because of DST, knowing where a clock is isn’t enough to calculate its UTC offset; you also need to consider what time of year it is.

Beyond being a hassle for datetime programmers, DST also has a massive quantifiable cost in both money and human lives. Every year, the lost productivity of people re-adjusting their sleep schedules costs about $275 million, and the sleep deprivation causes about 30 deaths from heart attacks, strokes, and sleepiness-induced fatal car crashes.

DST is an expensive, lethal, confusing, and inconsistent mess that should be abolished.

Seconds are a bad unit of time

As much as I pick on UTC, it accomplishes its stated goals admirably. It successfully manages the impossible task of reconciling caesium seconds with natural seconds.

But it shouldn’t have to.

Stable time and Earth-tracking time are fundamentally different things. Both are necessary, but they are simply not compatible. Without stable time, it would be impossible to describe things precisely or to coordinate consistently across the globe. Without Earth-tracking time, it would be impossible to describe the day/night cycle consistently and people would go insane from sleep deprivation as their circadian rhythms drifted out of sync. However, it simply doesn’t make sense to use the same time unit for both stable and Earth-tracking time. They are different and should have different units with different names that are substantially different in value so that people don’t conflate them.

Using a natural second when you meant to use a caesium second is objectively wrong and results in inconsistent behavior that causes real problems down the line. Had you accidentally used an hour instead of a second, you would instantly notice your mistake because the output would be immediately wrong by a factor of nearly four thousand. But because mixing up seconds is only wrong by two millionths of a percent, it’s very difficult to catch these kinds of mistakes until the errors have compounded over years.

The only reason that seconds continue to be universally used is cultural inertia, and seconds have a lot of cultural inertia. With the possible exception of base-10 mathematics, I can’t think of any other system that is more deeply rooted into modern human civilization. Everything depends on the second.

The second unites languages and cultures and measurement systems. Every server on the internet uses UTC timekeeping, every textbook and novel uses seconds to describe elapsed time, and every clock has a separate hand for hours, minutes, and seconds. Both metric and customary are defined in terms of seconds, which means that almost every manmade physical object manufactured in the last 200 years was built to a specification that used measurements that are based on the caesium second. All across the world, every road sign, milk jug, screw, skyscraper, and everything else relies on seconds.

Even if we had a better time unit, retrofitting all technology to the new standard would be an undertaking of such incomprehensible scale that it would make the Apollo Program look like a weekend Lego set.

There is no escape from the second, and there never will be.

The Marks System

…but what if there was?

I have an idea for a measurement and timekeeping system that uses neither caesium seconds nor natural seconds.

I call it the Marks system. It’s an eponym based on my last name, but I think that it sounds fittingly generic.

Disclaimer/Foreword

Firstly, even though I believe that the Marks system is genuinely better than our current second-based systems, I’m realistic about its chances of being adopted. This is not a naive, pie-in-the-sky manifesto. I realize how difficult it would be to adopt my system in practice. However, please try to suspend your disbelief about implementation feasibility.

Secondly, the terms and magnitudes that I use are just suggestions. The Marks system is more of a concept than an actual specification. The terms have plenty of wiggle room and are not set in stone; I changed my mind about a few of them in the process of writing this post. So if you object to something about the Marks system, please try to distinguish whether you’re objecting to the core concepts or just the naming conventions.

Planck Units

Planck units are the master units of reality. They’re not defined by silly human measurements, they’re made of other constants. If there is a God, He’s probably using these to boil His tea and put up His shelves.

Alexander McKechnie (@exurb1a)

Almost all measurement systems are based off of human convenience. For example, caesium seconds are based on the properties of caesium-133. Scientists could have chosen to base the second off of any other atom’s hyperfine transition frequency (although caesium-133 is cheap and very stable, which makes it convenient, which is why they chose it), so the choice of caesium-133 was arbitrary.

The exceptions to this are Planck units. Planck units are units that are defined exclusively using the fundamental universal properties of pure vacuum. These properties include the speed of light, the gravitational constant, and the Planck constant.

For example, to derive the Planck unit for time (which is called “Planck time”), all you have to do is multiply the reduced Planck constant by the gravitational constant, divide them by the speed of light raised to the fifth power, and then take the square root of the whole thing. This formula might sound arbitrary, but it isn’t. This formula is the only way to derive a unit of time from the properties of vacuum. If you asked someone who didn’t know about Planck units to invent a unit of time using only the properties of vacuum, they would (eventually) independently arrive at this same formula. The Planck units are unique, non-arbitrary, and fundamental, which is what make them special.

The problem with the Planck units is that, because they aren’t based on human convenience, they are pretty inconvenient. Shocking, I know.

For example, the Planck time is very, very, very, very small. When you express one Earth day in Planck times, you get approximately 1.6026x10^48. In word form, that’s over 1.6 million million billion billion billion billion Planck times. Obviously, this is an absurdly large and completely impractical number, which is why nobody uses Planck units.

The goal of the Marks system is to add a tiny bit of arbitrariness to make Planck units as convenient as the metric or customary systems.

Marks Prefixes

One of the best parts about the metric system is the SI prefixes. Rather than inventing entirely new words and ratios for each unit like the customary system does, the metric system uses power-of-ten prefixes to convert between its units. For example, because “kilo” means “1000”, a kilometer is exactly 1000 meters.

SI prefixes are very elegant and very coherent, and in my opinion they are far superior to the customary system’s seemingly random conversion ratios such as “1 mile equals exactly 5280 feet” and “1 ounce equals exactly 437.5 grains”.

However, there aren’t SI prefixes for every magnitude, most notably for 10,000 and 100,000. This might not seem important, but the Marks system really needs prefixes for these magnitudes in order to make convenient scales.

So I decided to extend the SI prefixes for a few important magnitudes that the official SI prefix specification omits.

When possible, I used existing unofficial SI prefixes, but a few magnitudes didn’t have any proposed prefixes so I had to make up my own. I took inspiration from the numeral systems of other cultures because they often have succinct, cool-sounding words for numbers.

Remember that these terms are just suggestions and are not set in stone.

| Magnitude | Prefix | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

10^4 |

Myria | A pre-existing prefix: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myria- |

10^5 |

Lakh- | Derived from Lakh, the Indian numbering system word for 100,000 |

10^7 |

Hebdo- | A pre-existing prefix: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hebdo- |

10^10 |

Rahng- | Derived from the romanized form of the Pinyin pronunciation of 穰, the Chinese short scale numeral for 10^10 |

10^-8 |

Ogdo- | Derived from the Greek word “ogdoos”, meaning “eighth”, because it’s ten to the minus eight |

10^-34 |

Triantessera- | Derived from the Greek phrase “triantatessera”, meaning “thirty-four”, because it’s ten to the minus thirty-four |

10^-44 |

Tetrakon- | Derived from the Greek word “tetrakontatessera”, meaning “forty-four”, because it’s ten to the minus forty-four |

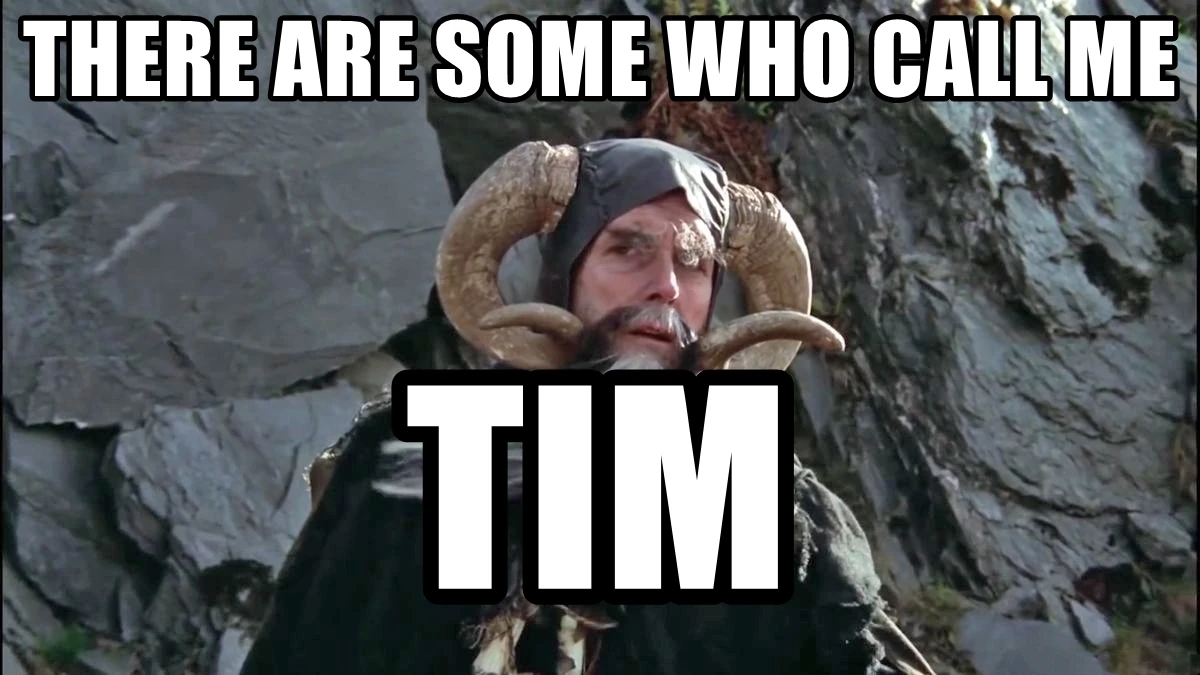

Tim

The tim is the fundamental unit of time for the Marks system. It’s pronounced /tɪm/ (exactly like how it looks).

Etymology

Tims get their name from the first three letters of the word “time”.

Definition

1 tim is defined as exactly 10^44 Planck times. This is approximately 5.391 caesium seconds.

Multiples

Combining tims with prefixes, you get a variety of supermultiples and submultiples to efficiently describe different time scales. The table below lists a few of the most useful ones.

| Unit | Tims | Equivalent |

|---|---|---|

| Tetrakontim | 10^-44 tims |

1 Planck time |

| Millitim | 0.001 tims | 5.39 milliseconds |

| Decitim | 0.1 tims | 0.54 seconds |

| Tim | 1 tim | 5.39 seconds |

| Decatim | 10 tims | 0.89 minutes |

| Hectotim | 100 tims | 8.98 minutes |

| Kilotim | 1,000 tims | 1.49 hours |

| Myriatim | 10,000 tims | 0.62 days |

| Lakhtim | 100,000 tims | 0.81 weeks |

| Megatim | 1,000,000 tims | 2.05 months |

| Hebdotim | 10,000,000 tims | 1.71 years |

| Gigatim | 1,000,000,000 tims | 1.71 centuries |

Conversions

Here are a few common second-based time units expressed in multiples of tims. They don’t map very evenly, which is intentional. More on that later.

| Unit | Tims |

|---|---|

| 1 second | 0.185 tims |

| 1 minute | 1.113 decatims |

| 1 hour | 0.667 kilotims |

| 1 day | 1.603 myriatims |

| 1 week | 1.122 lakhtims |

| 1 month | 0.488 megatims |

| 1 year | 0.585 hebdotims |

Examples

Here are a few common everyday durations expressed in tims.

| Duration | Tims |

|---|---|

| Hummingbird wing beat | 3 millitims |

| Human eye blink | 65 millitims |

| Average pop song | 36 tims |

| Time to cook an egg | 39 tims |

| REM sleep cycle | 2.7 hectotims (278 tims) |

| Average urban commute | 3.3 hectotims (336 tims) |

| Earth day | 1.6 myriatims (16,030 tims) |

| Moon orbit | 4.37 lakhtims |

| Average human lifespan | 42 hebdotims |

| Age of great pyramid | 26 gigatims (2,600 hebdotims) |

Why 10^44?

I chose to define 1 tim at exactly 10^44 Planck times because it results in a convenient human-scale amount of time. This was just an arbitrary choice on my part; 10^43 would also work. However, I think that 10^44 strikes a good balance between being too short and too long and it results in convenient multiples.

Are tims too long?

Tims are considerably longer than seconds. Rather than being 1 second long (approximately the frequency of a human heartbeat), a tim is over 5 seconds long. This is a massive departure from the fundamental time unit that everyone is used to. To count by tims, you’d say “one”, wait for what feels like ages, and then get to say “two”. I know that this seems alien and foreign and inconvenient.

However, it’s important to distinguish between cultural inertia and fundamental inconvenience. I believe that the reason that tims seem “wrong” is primarily inertia, which is a matter of implementation feasibility, which we agreed to suspend disbelief about. Imagine that we can magically just instantly make everyone acclimated to tims.

In this scenario, I think that tims would feel like a natural, convenient scale. Had I set 1 tim to equal 100 seconds or something, it would always be inconvenient even if everybody was magically used to it. There’s a range of acceptable values for a base unit of time that’s somewhere in between 0.1 seconds and 10 seconds, and I think that 5.4 seconds is within that range.

And if you need a less coarse unit of time than the tim, the decitim is quite convenient. It’s even more precise than the second without being overly precise like the millisecond.

And besides, you’ll see later why the fact that tims are different from seconds by such a significant amount is actually one of the greatest strengths of the Marks system.

Doesn’t this conflict with the name “Tim”?

That’s actually the second time I’ve heard that objection. It’s actually a pretty minute point when you compare it to how much semantic overlap second-based units have.

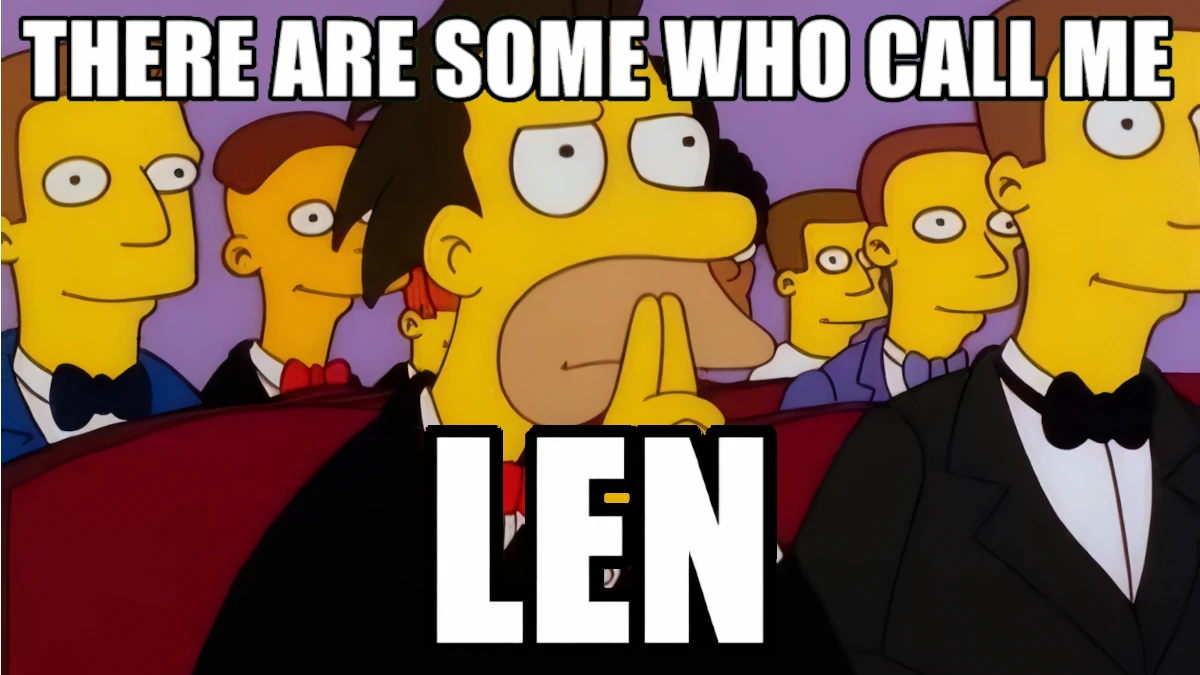

Len

The len is the fundamental unit of length for the Marks system. It’s pronounced /lɛn/ (exactly like how it looks).

Etymology

Lens get their name from the first three letters of the word “length”.

Definition

1 len is defined as exactly 10^34 Planck lengths. This is approximately 16.163 centimeters, or 6.36 inches.

Multiples

Combining lens with prefixes, you get a variety of supermultiples and submultiples to efficiently describe different distance scales. The table below lists a few of the most useful ones.

| Unit | Lens | Equivalents(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Triantesseralen | 10^-34 lens |

1 Planck length |

| Millilen | 0.001 lens | 0.161 millimeters |

| Decilen | 0.1 lens | 1.6 centimeters (0.6 inches) |

| Len | 1 len | 16 centimeters (6.3 inches) |

| Decalen | 10 lens | 1.6 meters (5.3 feet) |

| Hectolen | 100 lens | 16 meters (53 feet) |

| Kilolen | 1,000 lens | 161 meters (530 feet) |

| Myrialen | 10,000 lens | 1.6 kilometers (1.00 miles) |

| Lakhlen | 100,000 lens | 16 kilometers (10 miles) |

| Megalen | 1,000,000 lens | 161 kilometers |

Note that 1 decalen is approximately the height of an average adult human, and 1 myrialen is almost exactly 1 customary mile to within 1 part per hundred.

Examples

Here are a few common lengths expressed in lens. It’s a stylistic choice whether to primarily use len and myrialen or to use some of the more specific len multiples.

| Length | Lens |

|---|---|

| Width of a human hair | 464 microlens |

| Grain of table salt | 1.8 millilens |

| Paperclip | 2 decilens |

| Chicken egg | 3.5 decilens |

| Banana | 1.2 lens |

| Bowling pin | 2.3 lens |

| Electric guitar | 6 lens |

| Average human height | 1 decalen (10 lens) |

| African elephant | 4 decalens (40 lens) |

| Blue whale | 1.5 hectolens (150 lens) |

| Brooklyn Bridge | 3 kilolens (3,000 lens) |

| Grand Canyon | 2.7 megalens (270 myrialens) |

| Australia | 24 megalens (2,400 myrialens) |

Why 10^34?

I chose to define 1 len at exactly 10^34 Planck lengths because it results in a convenient human-scale length. Again, this was an arbitrary choice on my part, and there are other values that would have worked.

Maz

The maz is the fundamental unit of mass for the Marks system. It’s pronounced /mɑːz/ (with a long ‘a’ like in “car”).

Etymology

Maz get their name from “mass”, but it’s pronounced and spelled differently in order to make it distinct.

Had I named it “mas” to follow the truncation convention set by tims and lens, it would be impossible to tell “mass” and “mas” apart when spoken aloud. By backing the “a” and voicing the “s” (turning it into a “z”), the unit (maz) is phonetically and orthographically distinct from the dimensionality (mass).

Notably, unlike tims and lens which follow normal English pluralization rules, maz use the same word for both the singular and plural form: “maz”. I did this because the normal English plural form of “maz” is “mazes”, which is multisyllabic and is also a homograph for the plural form of “maze” (like a hedge maze).

Definition

1 maz is defined as exactly 10^8 Planck masses. This is approximately 2.176 kilograms, or 4.798 pounds.

Multiples

Combining maz with prefixes, you get a variety of supermultiples and submultiples to efficiently describe different mass scales. The table below lists a few of the most useful ones.

| Unit | Maz | Equivalents(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Picomaz | 10^-12 maz |

2 nanograms |

| Nanomaz | 10^-9 maz |

2 micrograms |

| Ogdomaz | 10^-8 maz |

1 Planck mass |

| Micromaz | 10^-6 maz |

2 milligrams |

| Millimaz | 0.001 maz | 2 grams |

| Decimaz | 0.1 maz | 217 grams (0.5 pounds) |

| Maz | 1 maz | 2.2 kilograms (4.8 pounds) |

| Decamaz | 10 maz | 22 kilograms (48 pounds) |

| Hectomaz | 100 maz | 218 kilograms (480 pounds) |

| Kilomaz | 1,000 maz | 2176 kilograms (4798 pounds) |

Note that, because 1 Planck mass is actually a surprisingly human-scale, the ogdomaz is not the smallest common multiple.

Examples

Here are the masses of a few common objects expressed in maz.

| Object | Maz |

|---|---|

| Paperclip | 0.5 millimaz |

| U.S. penny | 1.1 millimaz |

| Banana | 54 millimaz |

| Basketball | 287 millimaz |

| Macbook Air | 0.57 maz |

| Clay brick | 0.9 maz |

| Global average adult human (70kg/154lb) | 32 maz |

| Giant panda | 58 maz |

| Upright piano | 102 maz |

| Bluefin tuna | 206 maz |

| Compact car | 386 maz |

| TEU shipping container | 1 kilomaz (1,048 maz) |

| American school bus | 2.7 kilomaz (2,709 maz) |

Why 10^8?

I chose to define 1 maz at exactly 10^8 Planck masses because it results in a convenient human-scale mass. As usual, this was an arbitrary choice on my part, and there are other values that would have worked.

One reason that I chose 10^8 is that people are vain. For example, the reason that British imperial stone are still used is because they make the majority of human body weights fall between 6-25 stone. In customary pounds, this same range is 84-350 pounds. People prefer using measurement systems that make body weights have smaller numbers. Regardless of your opinion on this practice, it seems reasonable to meet people where they are.

Derived Units

Now that we have Marks units for the Big Three fundamental dimensionalities (time, length, and mass), we can combine them to create Marks units for the derived dimensionalities.

The Marks system uses metric-style 1:1 unit conversions. In other words, because “velocity” equals “length divided by time”, “1 unit of velocity” is exactly equal to “1 unit of length divided by 1 unit of time”.

To prevent this post from being 10,000 words long, I’m going to put a bunch of derived units in a table rather than giving each their own section. Each derived unit’s multiples follow the same standard SI conventions that the other Marks units use.

| Unit | Dimensionality | Definition | Pronunciation | SI Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vel | Velocity | len / tim |

/vɛl/ |

0.029 m/s |

| Ler | Acceleration | len / tim^2 |

/lɚ/ |

0.005 m/s^2 |

| Vol | Volume | len^3 |

/vɑl/ |

0.004 m^3 |

| Ary | Area | len^2 |

/ɛri/ |

0.026 m^2 |

| Tum | Momentum | maz * len / tim |

/tʌm/ |

0.065 kg m/s |

| Pul | Force | maz * len / tim^2 |

/pʊl/ |

0.012 N |

| Ner | Energy | maz * len^2 / tim^2 |

/nɛr/ |

0.002 J |

Notes

My suggested pronunciation for ler is /lɚ/. This is the natural pronunciation for most American English speakers (including me) that aligns with how we pronounce “acceleration”, but it contains a rhotic schwa, which can be difficult to pronounce if you speak almost any language/dialect other than American English or Mandarin Chinese. If you’re part of the 80% of humanity that doesn’t use rhotic schwas, I suggest pronouncing ler as /lɛr/ (rhymes with air).

You might notice that vel and vol are fairly similar phonetically and orthographically. I’m not particularly pleased with this and have considered many alternatives, but I’ve yet to come up with better terms. For example, “spe” (pronounced /spɛ/; derived from “speed”) doesn’t work as a substitute for vel because it looks orthographically incomplete and it’s difficult to pronounce its multiples; try saying “hectospe” out loud. “olu” (pronounced /ɑlu/; derived from “volume”) has the same problems. Feel free to email me any suggestions for better terms.

The reason that ary ends in “y” instead of “e” is because that would conflict orthographically with “are” (the extremely common verb) and make its pronunciation less obvious.

The reason that pul isn’t named “for” (truncated from “force”) is because that would conflict orthographically with “for” (the extremely common English preposition) and conflict phonetically with “4” (the number). Instead, I named the force unit after the word “pull” (a generic type of force). It’s not perfect, but it was better than the alternatives.

Expressing the speed of light

One of the convenient properties of Planck units is that, by definition, the speed of light is exactly 1 Planck length per Planck time. Because Marks units are simply supermultiples of the Planck units, it follows that the speed of light equals 10^10 lens per tim. Substituting vel for lens per tim, we get that 10^10 vel (1 rahngvel) is exactly equal to the speed of light. This is very convenient, and is much more elegant and memorable than “299,792,458 meters per second”.

Vernacular Multiples

Some of these derived units are inconveniently small. For example, 1 vel is glacially slow: approximately 0.067 miles per hour.

In cases like these, a convenient supermultiple should be used in common vernacular instead of the base unit, similar to how kilograms are used for most measurements instead of using grams directly. For example, rather than saying “cheetahs can run at 970 vels”, you would say “cheetahs can run at 9.7 hectovels”.

Of course, it would be great if the base units were human-scale, but they don’t naturally work out that way and it’s not worth losing the ease of 1:1 unit coherence by using arbitrary conversion ratios.

Note that many vernacular multiples have either the same number of syllables or fewer compared to their metric or customary counterparts, so they aren’t harder to say. For example, “hectovel” is three syllables, which is the same as “miles per hour” and shorter than both “meters per second” and “kilometers per hour”. Likewise, “kilovol” is three syllables, which is the same as “cubic feet” and shorter than “cubic meters”.

Temperature?

The Marks system doesn’t have a unit for temperature. This is for several reasons.

Firstly, none of the big three existing temperature systems (Celsius, Fahrenheit, and Kelvin) are defined in terms of seconds. The point of the Marks system is to provide Planck-based alternatives for the systems that depend on seconds. Temperature systems don’t depend on seconds, so they don’t need alternatives.

Secondly, temperature isn’t technically a true dimensionality. Temperature is just an expression of energy (via the Boltzmann constant), which there’s already a Marks unit for: ner. If you really insist on using Marks units for temperature, you can. For example, 100°C is approximately 2.6 attoner. If I created a new temperature unit, I would be repackaging an existing dimensionality in an arbitrary new unit with an arbitrary scale and an arbitrary name, which goes against the goals of the Marks system.

Thirdly, in order to make a convenient temperature system (i.e. one that isn’t zeroed at absolute zero), I would have to choose an arbitrary offset point to set as 0°. Even if I tried to be scientific and base it off of the properties of something (like how Celsius sets 0° as the freezing point of pure water), the substance and phase boundary that I would choose would still be arbitrary.

I think it’s better to just use the existing temperature systems rather than inventing a Marks system temperature system just for the sake of having one.

Tim Universal Time

Tim Universal Time (TUT) is a tim-based stable timekeeping system. It’s the Marks system’s answer to both UTC and Unix time. It’s pronounced /tʌt/ (“tut”, not “tee yoo tee”).

Definition

TUT is very simple: it’s just a single integer that increments at a rate of 1 tim per tim. No leap seconds, no time zones, no daylight saving, none of that. Just a simple counter.

For Humans

As I write this, 3,663,603 seconds have elapsed since the start of 2026. That almost certainly doesn’t mean anything to you, because no reasonable person expresses dates in terms of seconds. Instead, we list each unit individually: “February 12, 9:40:04 PM”.

But because tims use base-10, the decimal expression isn’t any less readable than if you listed each unit: “679,500 tims” vs “6 lakhtims, 7 myriatims, 9 kilotims, and 5 hectotims”.

This means that you don’t need to convert the TUT integer into a special human-readable format; you can just display the integer and people can read it because each digit corresponds to a tim multiple.

Depending on when you set TUT zero (more on that later), modern TUT values might have a lot of digits. The good news is that, for the average clock, you don’t need to display every digit. If you only display 4 digits, you can express up to 9,999 tims (approximately 0.62 days) before it overflows and resets. This is basically just the TUT equivalent of a 12-hour wall clock.

For Computers

The concept of “a simple integer counter to store the current time” has already been tested by Unix time: a 70s-era timekeeping system for computers that’s still very widely used today. Unix time is a 32-bit integer that increments by one second per caesium second. That “32-bit integer” part is a bit of computing jargon that basically means that it can only go up to 2,147,483,647 seconds, or 68 years. More on this later.

TUT uses signed 64-bit integers, which allows it to count both up and down by about 9 quintillion tims, which is approximately 114 times the current age of the universe.

TUT Zero

Now we’re faced with the difficult question of deciding when “000000… TUT” is.

The non-arbitrary choice is setting TUT zero at beginning of the universe. The advantage of this choice is that it eliminates the need for negatives. There’s no reason anyone would ever need to express a time before the Big Bang, so TUT will always be a positive number, which is pretty convenient. The disadvantage of this choice is that it’s not possible. We only know when the Big Bang occurred to about 117 teratims (20 million years) of precision. In order to get a truly accurate value for TUT zero, we would need to know it down to the individual tim. It doesn’t seem particularly likely that cosmology will suddenly advance 16 orders of magnitude in precision in the near future, so we can consider this not a viable option.

We could reference the Common Era (aka Anno Domini) calendar system that most of the world uses, setting TUT zero at the moment between 1 BCE and 1 CE. This would be the conventional choice.

Another viable option is using the Holocene calendar’s choice of a year zero: the approximate start of the Neolithic Revolution when early humans first discovered agriculture.

Since we’ll have to deal with negative TUT values regardless, we could also set TUT zero at a milestone in the recent past. The sky’s the limit here. A few suggestions:

- the moment that the Wright Flyer first flew at Kitty Hawk

- the moment that Neil Armstrong first set foot on the moon

- the moment that the first message was broadcast over the internet (technically, it was over ARPANET; the message was “lo”)

I don’t personally have any strong preference for what TUT zero should be. It should be set as whichever single moment in history is collectively decided to be the most important.

Sundial Time

The problem with TUT is that it doesn’t synchronize with the Earth’s rotation or its orbit. This is genuinely important for sleep schedules, farming, and many, many other things. Simply not having an Earth-tracking time system is unacceptable.

So I propose Sundial time. Sundial time is an Earth-tracking timekeeping system, similar to natural seconds. The length of the units is slightly different each day because the Earth’s rotation isn’t constant.

There are no leap seconds because there are no errors to correct; it stays in sync by definition. However, there are time zones. Kind of. Sundial time is localized, meaning that it varies based on your location. Even though different places in the world experience noon at different times, noon always occurs at the same time every day in Sundial time.

Etymology

The reason it’s called “Sundial time” is because it’s almost exactly how timekeeping worked for millennia using sundials.

The only reason people started caring about what time it was in other places was because of trains. With the invention of the locomotive, people could travel fast enough that they could basically race the Earth’s rotation. You could depart at noon, spend 6 hours traveling at 60 miles per hour, and find that your sundial read 5:33 when you arrived. This is because sundials are based on the position of the Sun in the sky, which varies by location. When you moved to the new location, you effectively shifted the sundial by 27 minutes.

This was very confusing for people at the time, so they created Railway time, a synchronized standard time system that was the same everywhere in the world. It was basically the precursor to UTC, and accordingly is the root of all UTC-related evil.

But now that we have TUT for the use cases that require stable timekeeping, we can use Sundial time for use cases that require Earth-tracking timekeeping.

Variable-length units

I know that having Sundial time be intentionally unstable sounds ridiculous. However, this is just a natural consequence of having an Earth-tracking time system. Earth’s rotation and its orbit vary in length, so their derived units must vary too. The only reason that UTC manages to have an Earth-tracking time system with stable units is because of its nightmarish complexity.

Technical Implementation

Sundial time can be determined using dedicated computer programs which, in a Marks-system-using future, every smart device would come preinstalled with. These programs can calculate the Sundial time for a given location at a given point in time, either in the past or future based on historical or extrapolated data.

You can also use a literal physical sundial. Seriously. The concepts are the same.

Specification

I don’t have a firm specification for Sundial time. As long as it’s Earth-tracking and doesn’t use seconds, it fits the bill. Sundial time is already very arbitrary because it uses Earth’s orbit rather than any fundamental constants, so it’s much more important to optimize for convenience than for non-arbitrariness. I leave designing the precise specification as an exercise to the reader.

…That being said, I do have a few hints/suggestions.

Firstly, I suggest using dal as the unit of Sundial time, pronounced /dɑːl/, like “doll” or like “dial” (from “sundial”) with a strong Southern twang.

Secondly, I suggest that 1 dal should be equal to 1/90,720 of a day. This is approximately 1.7665 decitims (0.95 caesium seconds). I selected 90,720 because it’s extremely divisible; it has 120 divisors (compared to 86,400’s mere 96 divisors). It’s also divisible by 7, which 86,400 is not.

You can stop suspending your disbelief now

“Adopting the Marks system would break 8 billion people’s unit intuitions. The lost productivity of people having to relearn basic measurements would surely amount to trillions of dollars at minimum.”

Yes, that’s a good point. It’d certainly be a very rough transition period. Those trillions of dollars could probably be put to a better use than switching to a more elegant measurement system.

“Re-manufacturing everything would not only be unimaginably expensive but it would also massively accelerate climate change by causing a huge spike in resource consumption.”

Yeah, that part would be pretty bad. I guess theoretically we could only update the specifications and leave the physical items intact, but that’d still be a monumental task and then every length, weight, speed, et cetera would have weird, uneven, and oddly precise values.

“The U.S. still hasn’t adopted the metric system, and the Marks system would be an even bigger change. Even if most of the world adopted the Marks system, there would almost certainly be a few holdouts. Rather than having two conflicting measurement systems, we’d have three.”

Another good point. Realistically, even if we somehow managed to get the world to run on tims and TUT behind the scenes, most normal people would probably refuse to switch away from existing measurement systems, even if lens and maz are better. This is pretty inconvenient for my argument, but I can’t hide behind “please suspend your disbelief” anymore. Cultural inertia is really difficult to overcome.

“This is just contrarianism and a solution in search of a problem.”

Ah, but that’s where you’re wrong. The Marks system actually solves a very real problem. Read on to the next section.

The Epochalypse

Remember how I said that Unix time can only go up to a certain number of seconds (approximately 68 years)? This is called the Unix epoch. After 2^31 seconds have passed since 1970, we’ll enter a new Unix epoch, causing Unix time to roll back to zero. This will happen on January 19, 2038.

This is called the Year 2038 problem. It’s similar in concept to the Y2K bug, where every computer that stored the current year as a 2-digit number believed that time had advanced from December 31, 1999 to January 1, 1900.

The main difference between then and now is that there are a lot more computers nowadays than there were in 1999. Like, a lot more, and we depend on them far more heavily.

The vast majority of modern computers use 64-bit Unix time, which won’t run out for nearly 300 billion years. Even among the systems that do use 32-bit Unix time, many have robust error handling and will realize that something is amiss and won’t actually think that it’s 1970.

But some of the most critical systems in the world don’t use modern computers, and many weren’t designed with robust error handling. The IRS and 92 of the top 100 global banks still primarily use mainframe computers from the 1960s. Their codebases contain many tens of millions of lines of code, most of it written in COBOL, which is a programming language where most of the people that knew it have retired and/or died.

Verifying that a system is actually safe from the 2038 problem is extremely difficult. Even if a system always stores time in 64 bits, if it converts that time into 32 bits even once for an intermediate step, the whole system is now vulnerable. Normally, programmers write tests for this kind of stuff. But tests don’t work on the 2038 problem because the system will always give the right answer until it suddenly doesn’t, and by then it’s too late. The only option is to read every single line of code and make sure that it doesn’t use 32-bit time even once.

The thing about the 2038 problem is that all it takes is one critical system, just one missed intermediate step that briefly uses 32-bit arithmetic, to cause it all to come crashing down.

Incompatibility as a feature

This is where the Marks system comes in.

Because TUT was never 32-bit, you can be sure that any system using TUT is 64-bit, and therefore is safe from the 2038 problem. So just by looking at a program and seeing which units it uses, you can determine if it is “possibly safe or possibly vulnerable and I have to read several million lines of code to be sure” or “definitely safe”.

There’s one big reason why rewriting systems to use tims might be genuinely easier than auditing every line of code: it lets you use empirical tests.

Accidentally using 32-bit seconds when you meant to use 64-bit seconds will still get you the right answer every time when you run the code, so it’s invisible to normal tests. There are specialized tests designed to catch 2038 bugs by setting the system clock to a date in the future, but they don’t encapsulate interactions with other servers and can still miss particularly subtle bugs. The fact that code runs successfully isn’t an indicator of whether or not it’s vulnerable to 2038. The only way to be sure is to carefully inspect every single line using expensive, slow, and mistake-prone humans.

In contrast, accidentally using seconds when you meant to use tims will cause the code to either fail outright or give an answer that’s wrong by a factor of more than 5, which you can easily test for. If tim-using code runs successfully, you know that it’s definitely safe from 2038. If it fails, you know that there’s definitely a problem with the code and you can fix it before it becomes a global problem. Rather than manually auditing tens of millions of lines of code, you can just… run the code.

Tims fill a specific niche created by Unix time’s technical debt, the fintech industry’s willingness to maintain 60-year-old mainframes, and the shortage of people who can properly audit COBOL code. Tims aren’t the only solution (nor are they necessarily the best one) but they are a genuinely viable solution.

Conclusion

In mid-2024, when I was 13, I was idly playing with Wolfram Alpha and asked it to compute the number of miles in a Planck length (I was very bored). My curiosity was piqued when I noticed that the result, 1.0043x10^-38, was within 1 part per hundred of a perfect magnitude. The idea occurred to me that we could use scaled-up Planck lengths to get the fundamentality of the Planck units and the convenience of the customary system. Over the next year and a half, I continued to think about this concept and about how a Planck-based measurement system would actually work. I thought about the magnitudes, pronunciations, multiples, and derived units that go into making a good unit system. I thought about the trade-offs of different timekeeping paradigms and how they would be used in different use cases. But perhaps most relevantly, I thought about how unimaginably difficult it would be to implement in practice.

If the Marks system or something similar is ever genuinely adopted in any capacity, I will be extremely surprised. I personally will continue using meters and seconds. The utility of using units that other people can understand far outweighs the utility of being able to express the speed of light as 10^10.

However, I do think that the Marks system is genuinely better in many respects to both the metric system and the customary system. Even if it will never be practically used, it’s a fun intellectual curiosity that’s interesting to think about and to write about. Thanks for indulging me, dear reader.

~Ethan